Legal professional Common Meese is a dwelling legend. On the age of 92, he has made extra contributions to the regulation than simply about any American who didn’t serve on the Supreme Courtroom. I barely scratched the floor of his exceptional profession in my 2022 Meese Lecture. But, in the event you ever meet Mr. Meese (and don’t name him Common!), one can find a humble and honest man. Meese isn’t one to boast about his voluminous accomplishments. Fortuitously, two of Meese’s shut associates within the Reagan Administration have put pen to paper, and recorded for posterity the Legal professional Common’s accomplishments.

Steve Calabresi and Gary Lawson have printed a brand new e-book, titled The Meese Revolution: The Making of a Constitutional Moment. The e-book tells the story of how Meese revolutionized constitutional regulation within the Division of Justice, and set the stage for the present originalist majority on the Courtroom. I’d extremely commend this superb e-book, which was launched right now. (I used to be capable of get a signed copy on the Federalist Society conference final week!)

Past the thorough therapy of Meese’s legacy, the e-book has numerous enjoyable tidbits that I loved. Considered one of them involved the case of Hodel v. Irving (1986). The e-book describes how Solicitor Common Charles Fried needed to struggle the “deep state” throughout the SG’s Workplace. This case offered the query of how broad the federal government’s taking energy was. Gary Lawson, who labored in OLC, favored a extra slim studying of the taking energy. However the profession legal professionals within the SG’s workplace used a much more capacious time period: plenary.

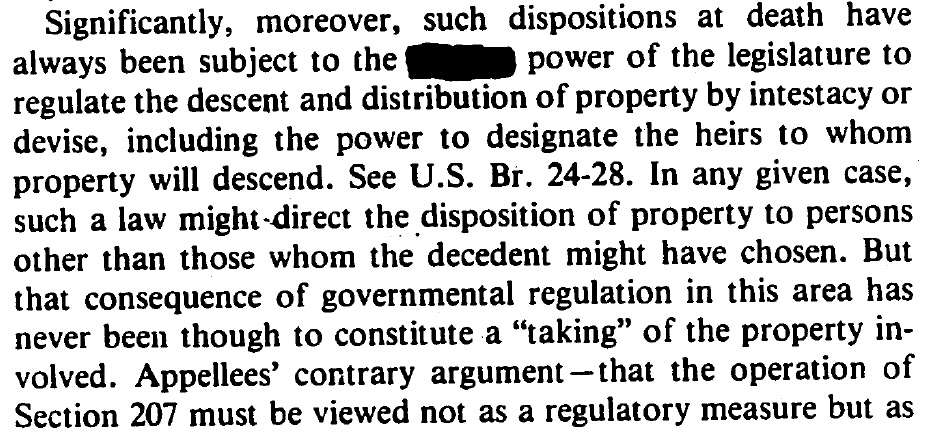

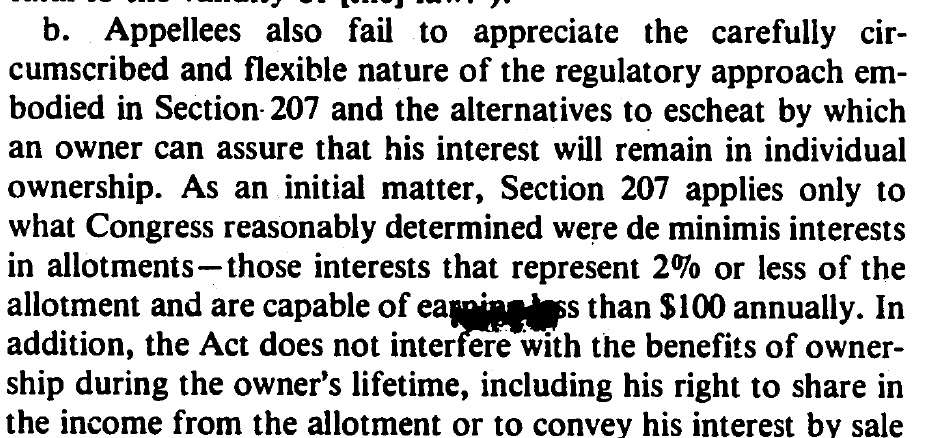

Within the early draft temporary for Hodel v. Irving, the case involving the Native American lands, Lawson was stunned to see an argument—apparently authored by profession SG legal professionals Ed Kneedler and Larry Wallace—saying, “Furthermore, each sovereign possesses the plenary energy to manage the style and phrases upon which property could also be transmitted at dying, in addition to the authority to prescribe who shall and who shall not be able to taking it” (emphasis added). A lot of this assertion was uncontroversial. Nobody doubts that governments can regulate the passage of property by will; there have lengthy been statutes defining easy methods to write a legitimate will, limiting to some extent the facility totally to disinherit sure members of the family, and so forth. The important thing to the draft temporary’s argument was the phrase “plenary.”

Nonetheless, the political appointees in DOJ objected to the phrase “plenary”:

Within the early draft temporary for Hodel v. Irving, the case involving the Native American lands, Lawson was stunned to see an argument—apparently authored by profession SG legal professionals Ed Kneedler and Larry Wallace—saying, “Furthermore, each sovereign possesses the plenary energy to manage the style and phrases upon which property could also be transmitted at dying, in addition to the authority to prescribe who shall and who shall not be able to taking it” (emphasis added). A lot of this assertion was uncontroversial. Nobody doubts that governments can regulate the passage of property by will; there have lengthy been statutes defining easy methods to write a legitimate will, limiting to some extent the facility totally to disinherit sure members of the family, and so forth. The important thing to the draft temporary’s argument was the phrase “plenary.”

So what did Fried do? He pulled out a marker and redacted the phrase “plenary” from the temporary:

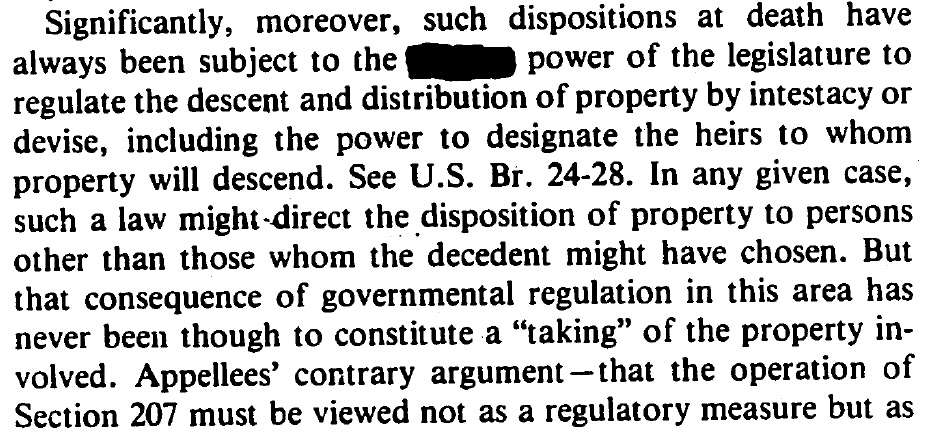

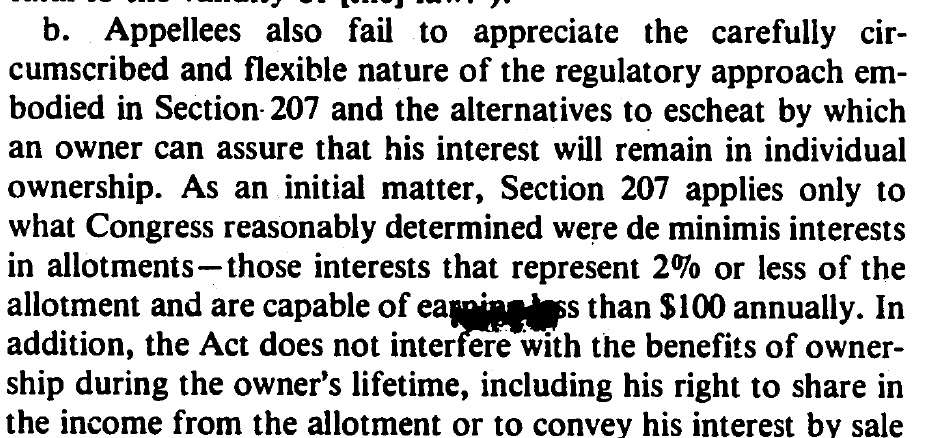

Recall how Fried talked about that he generally acquired briefs from his workers with little or no time to make revisions. This time, he acquired printed copies of the temporary—a number of dozen of them—able to be filed with the Supreme Courtroom. The temporary described the federal government’s “plenary” energy over testation, together with its means to abolish altogether folks’s energy to move down their property. There was then no solution to make revisions to the briefs; they had been in ultimate printed type. Charles Fried discovered a method. On the eve (actually the eve) of submitting the briefs within the Supreme Courtroom, he took a marker and personally, by hand, blacked out the phrase “plenary” in each printed copy of the temporary. In the present day, when every little thing is digitized, this exceptional occasion is in peril of disappearing. But when one can find a tough copy of the temporary (there are 9 depositories for printed SG briefs throughout the nation), or a PDF that precisely reproduces the unique doc, one will see a hand-crafted deletion in each copy. This was Charles Fried at his most interesting—and the profession workers within the SG’s Workplace doing what it did.

Once I learn this passage, I instantly emailed the superb librarians on the South Texas School of Regulation to search out the temporary. Fortuitously, they’ve microfiched copies of Supreme Courtroom briefs from the Nineteen Eighties. They usually discovered the Hodel reply temporary:

On web page 5 of the temporary, you may see the redaction:

And the marker bled by way of to web page 6:

In case you pull up the temporary on Westlaw, there are two query marks within the place of the redaction

The story will get even higher. Justice O’Connor requested Ed Kneedler about this subject throughout oral argument:

The story will get even higher. Justice O’Connor requested Ed Kneedler about this subject throughout oral argument:

There’s a coda to the story. Even after Fried’s heroic effort at injury management, if one held up the marked-out portion of the printed briefs to the sunshine, one might faintly see the phrase “plenary” beneath. At oral argument in Hodel v. Irving, when Ed Kneedler offered the federal government’s case, Justice O’Connor requested, “Mr. Kneedler, are there any limits in your view as to what the federal government can do or change in regards to the descent of property belonging to Indians? Do you assume the federal government has plenary energy to actually make any type of a regulation?” (Lawson was within the gallery throughout this argument and needed to choke again laughter when Justice O’Connor various her usually well mannered and soothing tone to provide pointed emphasis to the phrase “plenary.”) Kneedler replied, little question as he had been ordered to answer, “No, our submission doesn’t go practically that far.” He then added, nevertheless, that “[t]he Courtroom has described the facility of the legislature over the descent of property in very broad phrases, suggesting that the best to move property and to obtain it by descent or by will is creation of statute and never a pure proper, it’s a privilege that may be conditioned and even abolished, however the Courtroom has by no means been confronted with a state of affairs the place it needed to handle that, and it is not right here.” A easy “no,” after all, would have sufficed, however Kneedler insisted on emphasizing at the very least the likelihood that governments might abolish the switch of property at dying. Justice O’Connor adopted up: “Nicely, do you’re taking the place that it may be abolished?” Kneedler responded, “That’s not a part of our submission right here, no,” and sought to elucidate the restricted scope of the regulation really at subject within the case.

A tremendous story, from a tremendous e-book.